"[Carlo] says Reno is just like Las Vegas, but bigger, with more lights. Which must be quite a lot, because where I live, it never gets really dark at night. I can always see the Strip glowing, usually kind of white but sometimes kind of pink. And there is a big light on top of a pyramid that points right at our apartment, like a laser. Tirana is afraid of that light, but I tell her that it's a spotlight shining at us so we could never be lost. I suppose God doesn't really need a spotlight to know where Tirana and I are, but I don't know that much about God, and I think it is good to have that backup light." -Laura McBride, We Are Called to Rise

Among the tufts of bermudagrass and the burned red dirt of Las Vegas, Nevada, four individuals are struggling to glean beauty from heartbreak. There's Bashkim Ahmeti, a second-grader whose Albanian refugee parents operate an ice cream truck until disaster strikes during a routine traffic stop. Specialist Luis Rodriguez-Reyes returns home after a traumatic deployment to Iraq. Middle-aged housewife Avis Briggs learns of her husband's affair and must sweep up the scraps of her marriage while working to steady the emotions of her troubled soldier-turned-police officer son, Nate. And Roberta Weiss, a volunteer Court Appointed Special Advocate for children in splintered households, is learning how to mend the broken parts of someone else's life while doing the same with her own.

Las Vegas proves the perfect setting for a story that knits together death and rebirth, vast, isolating expanses and suffocating claustrophobia. In the 1820s, members of a Spanish scouting expedition stumbled upon a verdant land teeming with rivers and artesian wells. Christened Las Vegas ("the meadows"), the region became a popular water stop for wagon caravans and, later, trains en route to destinations such as Los Angeles or Albuquerque. Over time, the extensive network of rivers sank into the ground and Las Vegas grew parched, able to sustain only the hardiest of plant and animal species--a once-pulsating, fertile corner of the earth that literally collapsed into itself.

In Laura McBride's debut novel, the idea of Las Vegas as nurturer and punisher is echoed in the stories of each character. The city is a sanctuary to Bashkim and his family after his father is held as a political prisoner in Albania. For Luis, it is the suburbs beyond the buzz of the Strip that help to steady his war-addled mind. Avis has found comfort and stability in the decades spent in one single home. Roberta sees life and hope particularly among those who appear to be caving into themselves just as the city once did. But what Las Vegas giveth, Las Vegas can taketh away. By the end of the novel, Bashkim has suffered a terrible loss and finds himself and his sister dropped unceremoniously into the foster care system. Luis returns from war haunted by the image of the young boy he killed, only to encounter another boy--Bashkim--in a region that, aside from the buildings and the people, could be the very desert battlefield he left behind. After worrying that she had chosen to raise her son in a place nicknamed "Sin City," Avis is starting to understand the many manifestations of the phrase. Roberta finds that despite her best intentions, she is helpless to match the needs of thousands of children impacted in one way or another by the city's vices.

Somehow, though, through the violence and the racism and the post-traumatic stress, despite Las Vegas's sinking rivers (and, perhaps, because of them), life continues. Spotted knapweed spreads across the hillsides like a blush. Barrel cacti and purple arrowweed spread their roots in the dry, arid soil and do not mourn the rain. Mexican wolves and bighorn sheep and collared peccaries roam the harsh landscape. And Bashkim and Luis, Avis and Roberta, are learning to settle, too, each one in an environment that is challenging but not altogether unforgiving. Each one in an environment that is maybe exactly what they need to thrive.

Off the Beaten Page

Every story has a place. Every place has a story.

Friday, September 19, 2014

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Zanesville

"We live in a factory town, Zanesville, Illinois, the farm implement capital of the world. This means nothing to Felicia and me; we care only about our own neighborhood, everything between our two houses, a handful of potholed streets and alleys lined with two-story homes and one-car garages. We have a couple of busy intersections with four-way stop signs, a red brick barbershop, a corner tavern, a taxidermist, a family who paved their backyard and painted it green, and a house where the garage has been turned into a tap-dance studio. Otherwise, it's all the same, every block, through our neighborhood and the neighborhoods beyond." -Jo Ann Beard, In Zanesville

Zanesville, Illinois in the 1970s is a time of disillusionment for the precocious 14-year-old narrator of Beard's second novel. Babysitting is a bust after the fire department is called to extinguish a blaze. Marching band is clearly ridiculous--who in their right mind would wear an eight-inch-tall hat that leaves her ears exposed? And, to top it all off, there's no way to say "fudge" with a British accent.

Growing up in a town in which ordering pizza and having it sent to the parochial kid's house just to see whether his parents would actually pay for it doesn't exactly open up a world of opportunities for the narrator. But counterintuitive as it may seem, whitewashed, cookie-cutter Zanesville is an adventure because of, not despite, its lifelessness. After all, a town with a population of approximately 450 (plus a few sickly stray kittens) leaves practically everything to the imagination. It's no wonder that all the residents, not just the restless adolescents, do what they can to make things a bit more...colorful. "Over on my block," the narrator explains, "the semi-interesting people include a woman who comes outside and washes her dog's face with a dishcloth every hour or so, and a widowed man who is so gigantic he needs a kitchen chair to get to his car.... We also have a neighbor named Fudgy, or Uncle Fudge, a barber who has no hair of his own." And that, says the narrator, is about it. Lots of dogs, lots of empty spaces. It seems inevitable, then, that she and her best friend Felicia spend their school days launching projectiles at the lunch lady, hoping to be sent to detention where they can sit next to the boys they think have crushes on them and write notes back and forth about whose boy has the softer-looking hair.

Zanesville, Illinois in the 1970s is a time of disillusionment for the precocious 14-year-old narrator of Beard's second novel. Babysitting is a bust after the fire department is called to extinguish a blaze. Marching band is clearly ridiculous--who in their right mind would wear an eight-inch-tall hat that leaves her ears exposed? And, to top it all off, there's no way to say "fudge" with a British accent.

Growing up in a town in which ordering pizza and having it sent to the parochial kid's house just to see whether his parents would actually pay for it doesn't exactly open up a world of opportunities for the narrator. But counterintuitive as it may seem, whitewashed, cookie-cutter Zanesville is an adventure because of, not despite, its lifelessness. After all, a town with a population of approximately 450 (plus a few sickly stray kittens) leaves practically everything to the imagination. It's no wonder that all the residents, not just the restless adolescents, do what they can to make things a bit more...colorful. "Over on my block," the narrator explains, "the semi-interesting people include a woman who comes outside and washes her dog's face with a dishcloth every hour or so, and a widowed man who is so gigantic he needs a kitchen chair to get to his car.... We also have a neighbor named Fudgy, or Uncle Fudge, a barber who has no hair of his own." And that, says the narrator, is about it. Lots of dogs, lots of empty spaces. It seems inevitable, then, that she and her best friend Felicia spend their school days launching projectiles at the lunch lady, hoping to be sent to detention where they can sit next to the boys they think have crushes on them and write notes back and forth about whose boy has the softer-looking hair.

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Jakarta

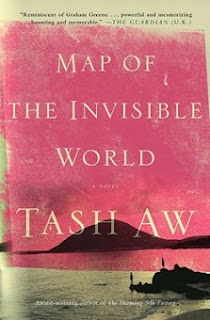

"His classmates tore the pages from his books and folded them into paper airplanes that they launched into the air with sharp spearing motions. Adam watched as bits of the atlas glided past him: The pink and green of the United States floated dreamily in circles until it stubbed its nose on the blackboard and fell abruptly to the ground; the whiteness of the Canadian tundra swept out of the window in an arc, into the dusty sunlight; and the silent mass of the Pacific Ocean that Adam loved so much, dotted with islands (Fiji? Tahiti?) lay on the cracked cement floor, waiting to be trampled." -Tash Aw, Map of the Invisible World

It's not that Adam de Willigen was abandoned in an orphanage with his older brother Johan when they were children, or that Johan was adopted by a wealthy Malaysian couple who chose to leave the sickly Adam behind. It's not that Adam's adoptive father Karl, Dutch by birth, is hauled off by Indonesian authorities in the summer of 1964 at the height of the communist scare. It's not even that Adam must leave his house on the small island of Perdo for the political dangers of Jakarta when his father disappears. It's that after 16 years, Adam cannot recognize "home" and all it signifies as a concept that has ever belonged to him.

In Jakarta there is Margaret Bates, an American anthropologist whose photographs Adam finds among his missing father's possessions. Believing Margaret to have information on Karl's whereabouts, Adam climbs aboard a vessel leaving the port of Perdo and docks in Jakarta, the capital and largest city in the Indonesian archipelago. But the city he encounters is not the magnificent metropolis it once was; Jakarta is in political disarray, embittered by a territorial dispute with newly independent Malaysia and in the midst of purging a half-million citizens accused of being communists.

Jakarta's alleys are "filled with the aroma of incense and cooking and blocked drains" and President Sukarno is virtually helpless to prevent violent civil war from paralyzing his country. Buildings are crumbling. Rubble-strewn streets have become public urinals. American cigarettes are tools of bribery. Political unrest has settled itself like a dense and reeking fog over the capital and it is here, among the hatred and wreckage of once-great institutions, that Adam must find his father and slowly begin to reconcile his mind with the existence of home.

It's not that Adam de Willigen was abandoned in an orphanage with his older brother Johan when they were children, or that Johan was adopted by a wealthy Malaysian couple who chose to leave the sickly Adam behind. It's not that Adam's adoptive father Karl, Dutch by birth, is hauled off by Indonesian authorities in the summer of 1964 at the height of the communist scare. It's not even that Adam must leave his house on the small island of Perdo for the political dangers of Jakarta when his father disappears. It's that after 16 years, Adam cannot recognize "home" and all it signifies as a concept that has ever belonged to him.

In Jakarta there is Margaret Bates, an American anthropologist whose photographs Adam finds among his missing father's possessions. Believing Margaret to have information on Karl's whereabouts, Adam climbs aboard a vessel leaving the port of Perdo and docks in Jakarta, the capital and largest city in the Indonesian archipelago. But the city he encounters is not the magnificent metropolis it once was; Jakarta is in political disarray, embittered by a territorial dispute with newly independent Malaysia and in the midst of purging a half-million citizens accused of being communists.

Jakarta's alleys are "filled with the aroma of incense and cooking and blocked drains" and President Sukarno is virtually helpless to prevent violent civil war from paralyzing his country. Buildings are crumbling. Rubble-strewn streets have become public urinals. American cigarettes are tools of bribery. Political unrest has settled itself like a dense and reeking fog over the capital and it is here, among the hatred and wreckage of once-great institutions, that Adam must find his father and slowly begin to reconcile his mind with the existence of home.

Monday, February 6, 2012

Yellowknife

"At the sound of the loons, she automatically pressed record and stood listening to birds that mated for life, their beautiful mad laughter. What held her eye, however, was the look of her hand on the microphone. So weathered and chapped compared to the silver-metallic stem she was holding carefully, no rings on her fingers to click against the metal and transfer to the dark spool of her tape, her equipment solid and unchanging and Japanese, her veins purply under the roughened, reddish-brown skin." -Elizabeth Hay, Late Nights on Air

"At the sound of the loons, she automatically pressed record and stood listening to birds that mated for life, their beautiful mad laughter. What held her eye, however, was the look of her hand on the microphone. So weathered and chapped compared to the silver-metallic stem she was holding carefully, no rings on her fingers to click against the metal and transfer to the dark spool of her tape, her equipment solid and unchanging and Japanese, her veins purply under the roughened, reddish-brown skin." -Elizabeth Hay, Late Nights on AirGwen Symon lives for the day when she can produce a radio drama like "Death in the Barren Ground," a story she'd heard as a young girl about the Englishman John Hornby who starved to death in the Barrens in arctic Canada in 1927. After learning that Yellowknife's "one-thousand-watt station" doesn't do drama, Gwen must adjust to station manager Harry Boyd's decision to put her on the air as a newsreader. Gwen joins a station of eccentric personalities: a sultry Dutch beauty named Dido Paris who fancies herself the apex of the radio world; Eleanor Dew, the sensitive receptionist; temperamental Eddy; middle-aged photographer Ralph; and Harry, who fell in love with Dido the first time he heard her voice over the airwaves and whose devotion to his station is bested only by his dream for more. In the wake of a series of tragedies, unsure of their futures in Yellowknife and on the radio, Gwen, Eleanor, Ralph, and Harry embark on a canoe trip to trace the path of Hornby's fated trek through the vast, frozen Canadian wilderness.

In the 1970s, when Hay's novel is set, the town of Yellowknife in Canada's Northwest Territories (NWT) was a relic of premodern vanity, of the time before highrises and shopping malls and four-lane arterials when you could stroll up the hill and see nothing but rivers and lakes and undeveloped frozen tundra in all directions. Yellowknife lies just 250 miles south of the Arctic Circle, and though it averages a brisk -16 degrees Fahrenheit every January, there is something ethereal in the sky's perpetual glow, the "constant light [that is] like endless caffeine."

Ten thousand people inhabited the rocky enclave on the shore of the Great Slave Lake, the deepest of its kind (2,010 feet) in North America. By 2006, the population had nearly doubled. As the NWT's capital city, Yellowknife now accounts for approximately half the population of the entire territory.

The tundra surrounding the capital is entirely stippled with miniature lakes and an aerial view in winter shows the landscape as 440,000 miles of white with frozen blue pinpricks so close and infinite that it seems you could hop from one to another for all eternity without ever setting foot on solid ground. Yellowknife is isolated but not desolate. It has bars and cafes, hair salons and heritage museums. It hosts music festival and ice sculpting contests and dogsled races. It has modern automobiles and magazine offices. It is an arctic sentinel, guarding its caribou and polar bears, its musk oxen and snow owls, from the gritty fingertips of those who seek to exploit.

But most of all, most of all it is a place of solitude and redemption, where second chances come in the unexpected form of a job playing music and reading poetry on late-night radio.

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Manaus and the Amazon

"But Marina had already left him, and she understood that in life a person was only allowed one trip down to hell. There was no going back to that place, not for anyone." -Ann Patchett, State of Wonder

Her colleague is dead in the Amazon. Marina Singh has the letter in her hand. Fever and delirium, the macabre gift of mosquito-borne malaria. Dr. Eckman's death is a tragedy, the letter says. A tragedy but only a minor setback for Vogel, a pharmaceutical company conducting fertility research on the Lakashi tribe along the Rio Negro in Brazil. Begged by Dr. Eckman's wife to prove her husband's death and ordered by her boss to monitor the progress of the company's research, Marina boards a flight bound for Manaus, Brazil and finds herself, weeks later, on a pontoon gliding deep into the heart of the Amazon.

Manaus, or "Mother of the Gods," is the capital of the Amazonas and the largest city in northern Brazil. It's hard to imagine a city located squarely within the boundaries of the Amazon Basin having multiple-lane roads and bars with outdoor stages, but such is the way of life in Manaus. Equally incongruous with its rainforest setting is Teatro Amazonas, the city's 115-year-old opera house that was built with roofing tiles from Alsace, furniture from Paris, steel walls shipped in from England, marble tiles and columns from Italy, and water for its drinking fountains airlifted north from Antarctica. (Just kidding about that last one. I hope.) If the opera house is too much of a cultural experience for those wondering how the heck there's an opera house in the Amazon, the Parque do Mindu might be just the perfect pre-jungle tour nature experience. The park covers 33 hectares near the city's center and is home to Manaus's own endemic species of tamarin - the sanguinus bicolor. Just downriver, the black water of the Rio Negro meets the white water of the Rio Solimoes and the two flow, magnetically parallel, for several kilometers before mixing.

Manaus rests at the mouth of the Rio Negro, one of many rivers that curls its way deep into the jungle fog and foliage. For many, the city exists as a glorified way station - its supply stores and cheap hotels essential stops for tourists awaiting their pontoon ride into the heaving soul of the Amazon.

And oh, the Amazon. Rivers so deep and murky there's no telling what lurks in their waters. Bullet ants the size of a child's thumb have a sting as powerful and debilitating as a gunshot. Though nonvenomous, 20-foot anacondas can make quick work of wringing the life out of a healthy, unsuspecting tourist on the worst day of his life. Contracting malaria is as easy as letting a mosquito land on your bicep. The native tribes are often hostile, swiftly answering the tourist problem with a deluge of razor-sharp arrows. At its worst, the jungle is something south of hospitable and somewhere south of hell.

So what would possess a person to trek beneath its deadly green veil? Its size, for starters. The Amazon covers 1.7 billion acres (roughly the size of the contiguous United States) and dips into nine countries, containing more than half of the world's remaining rainforests. The Amazon River is discharges more water than any other river in the world and is bested in length, at 4,080 miles, by only the Nile. Tributaries traverse the basin like bloodlines, each feeding its own delicate and complex ecosystem. Here, in the flooded forests and savannas of the largest rainforest on the planet, indigenous tribes have created entire civilizations that are invisible to the rest of the world, protected by the green canopy of Kapok and Brazil nut trees.

And just as a quick editorial note, allow me to suggest that you not set out on your own in a paddle boat down a river filled with piranhas and freshwater bull sharks. Marina Singh's mission may have been motivated by science and the death of her colleague, but unless you're equipped to handle a month-long stay with a remote Amazonian tribe whose women can give birth into their seventies, I'd urge you to book flights to, say, Jamaica instead.

Manaus, or "Mother of the Gods," is the capital of the Amazonas and the largest city in northern Brazil. It's hard to imagine a city located squarely within the boundaries of the Amazon Basin having multiple-lane roads and bars with outdoor stages, but such is the way of life in Manaus. Equally incongruous with its rainforest setting is Teatro Amazonas, the city's 115-year-old opera house that was built with roofing tiles from Alsace, furniture from Paris, steel walls shipped in from England, marble tiles and columns from Italy, and water for its drinking fountains airlifted north from Antarctica. (Just kidding about that last one. I hope.) If the opera house is too much of a cultural experience for those wondering how the heck there's an opera house in the Amazon, the Parque do Mindu might be just the perfect pre-jungle tour nature experience. The park covers 33 hectares near the city's center and is home to Manaus's own endemic species of tamarin - the sanguinus bicolor. Just downriver, the black water of the Rio Negro meets the white water of the Rio Solimoes and the two flow, magnetically parallel, for several kilometers before mixing.

Manaus rests at the mouth of the Rio Negro, one of many rivers that curls its way deep into the jungle fog and foliage. For many, the city exists as a glorified way station - its supply stores and cheap hotels essential stops for tourists awaiting their pontoon ride into the heaving soul of the Amazon.

And oh, the Amazon. Rivers so deep and murky there's no telling what lurks in their waters. Bullet ants the size of a child's thumb have a sting as powerful and debilitating as a gunshot. Though nonvenomous, 20-foot anacondas can make quick work of wringing the life out of a healthy, unsuspecting tourist on the worst day of his life. Contracting malaria is as easy as letting a mosquito land on your bicep. The native tribes are often hostile, swiftly answering the tourist problem with a deluge of razor-sharp arrows. At its worst, the jungle is something south of hospitable and somewhere south of hell.

So what would possess a person to trek beneath its deadly green veil? Its size, for starters. The Amazon covers 1.7 billion acres (roughly the size of the contiguous United States) and dips into nine countries, containing more than half of the world's remaining rainforests. The Amazon River is discharges more water than any other river in the world and is bested in length, at 4,080 miles, by only the Nile. Tributaries traverse the basin like bloodlines, each feeding its own delicate and complex ecosystem. Here, in the flooded forests and savannas of the largest rainforest on the planet, indigenous tribes have created entire civilizations that are invisible to the rest of the world, protected by the green canopy of Kapok and Brazil nut trees.

And just as a quick editorial note, allow me to suggest that you not set out on your own in a paddle boat down a river filled with piranhas and freshwater bull sharks. Marina Singh's mission may have been motivated by science and the death of her colleague, but unless you're equipped to handle a month-long stay with a remote Amazonian tribe whose women can give birth into their seventies, I'd urge you to book flights to, say, Jamaica instead.

Friday, January 6, 2012

Shanghai

"All those old ideas about the zodiac, food, and other traditions give me comfort, but I'm not the only one looking backward for consolation. May is bright, effervescent, and undeniably exquisite at twenty, but her life--even though she gets to go to movie sets and dress up--is not what she envisioned back when we were beautiful girls in Shanghai." -Lisa See, Shanghai Girls

For Pearl and May, daughters of a wealthy Chinese businessman, nothing could be more exotic than growing up in 1930s Shanghai, "the Paris of Asia." They attend extravagant parties with other members of high society. They model for a calendar painter and shout orders for miso soup from the street vendor out the window, hoisting the brimming bowls up to the painter's studio with a makeshift pulley. They dine on "stewed plums besprinkled with licorice powder" and "steamed rice cakes made with rugosa rose and white sugar." Having been born into a modernized China--a China in which footbinding is against the law and marriages are now seldom arranged--they dream of running free and marrying for love.

They never could have imagined that their father would gamble away his family's wealth, that to repay his debts to the "monkey people" (or "dwarf bandits") he would sell his daughters into marriages they did not choose. With their futures out of their control and with World War II leaving its calling card along the streets of Shanghai in the form of gutted buildings and mangled flesh, May and Pearl are forced to leave their beloved city for a life across the ocean in "Haolaiwu"--Hollywood.

The Shanghai of today is both a stark departure from and a vestige to May and Pearl's Asian Paris. The Huangpu River divides the city in two. Puxi, a homage to the Shangai of the 1800s, sits on the west side while Pudong, a hub of futuristic high-rises (like the Oriental Pearl Tower) spans the river's east bank.

Shanghai's ornately decorated temples and monasteries are proof that even a fast-paced, avant-garde city honors its antiquity. First constructed in 242 AD and rebuilt in 977, the recognizable Longhua Pagoda was a favorite destination of See's protagonists and remains the only pre-modern structure in modern Shanghai. Teahouses, manicured gardens, and boisterous street vendors are the soul of old Shanghai--the Shanghai in which May and Pearl flew kites and rode in rickshaws and pedaled bicycles down quiet tree-lined avenues. Largely pedestrianized Nanking Road, today the busiest shopping street in the world, was for May and Pearl the place to experience Shanghai culture. "May and I stroll up Nanking Road," Pearl explains, "avoiding the refugees and eyeing Shanghainese and Shanghailanders to see what they're wearing." (Shanghainese were people native to the city while Shanghailanders were foreigners who settled there before the 1950s.)

After Chinatown was established in their adopted city of Los Angeles in 1938, the homesick sisters implanted themselves in the food and dress and culture of the life they had left behind. In Shanghai, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek had failed to defend the city from Japanese invasion and by the end of 1937 the city had fallen. Chairman Mao rose to power and whispers of a newly red China rippled throughout the streets of LA's Chinatown. Hearing of the destruction and corruption of their country, May and Pearl vow to never return. They find power in their resolve. What they cannot control, though, is Joy--Pearl's college-educated, American-born daughter who feels it is her duty to witness the changes in China for herself.

It is here that See leaves the reader, but only long enough to close the book, take a deep breath, and open Dreams of Joy, the sequel.

For Pearl and May, daughters of a wealthy Chinese businessman, nothing could be more exotic than growing up in 1930s Shanghai, "the Paris of Asia." They attend extravagant parties with other members of high society. They model for a calendar painter and shout orders for miso soup from the street vendor out the window, hoisting the brimming bowls up to the painter's studio with a makeshift pulley. They dine on "stewed plums besprinkled with licorice powder" and "steamed rice cakes made with rugosa rose and white sugar." Having been born into a modernized China--a China in which footbinding is against the law and marriages are now seldom arranged--they dream of running free and marrying for love.

They never could have imagined that their father would gamble away his family's wealth, that to repay his debts to the "monkey people" (or "dwarf bandits") he would sell his daughters into marriages they did not choose. With their futures out of their control and with World War II leaving its calling card along the streets of Shanghai in the form of gutted buildings and mangled flesh, May and Pearl are forced to leave their beloved city for a life across the ocean in "Haolaiwu"--Hollywood.

The Shanghai of today is both a stark departure from and a vestige to May and Pearl's Asian Paris. The Huangpu River divides the city in two. Puxi, a homage to the Shangai of the 1800s, sits on the west side while Pudong, a hub of futuristic high-rises (like the Oriental Pearl Tower) spans the river's east bank.

Shanghai's ornately decorated temples and monasteries are proof that even a fast-paced, avant-garde city honors its antiquity. First constructed in 242 AD and rebuilt in 977, the recognizable Longhua Pagoda was a favorite destination of See's protagonists and remains the only pre-modern structure in modern Shanghai. Teahouses, manicured gardens, and boisterous street vendors are the soul of old Shanghai--the Shanghai in which May and Pearl flew kites and rode in rickshaws and pedaled bicycles down quiet tree-lined avenues. Largely pedestrianized Nanking Road, today the busiest shopping street in the world, was for May and Pearl the place to experience Shanghai culture. "May and I stroll up Nanking Road," Pearl explains, "avoiding the refugees and eyeing Shanghainese and Shanghailanders to see what they're wearing." (Shanghainese were people native to the city while Shanghailanders were foreigners who settled there before the 1950s.)

After Chinatown was established in their adopted city of Los Angeles in 1938, the homesick sisters implanted themselves in the food and dress and culture of the life they had left behind. In Shanghai, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek had failed to defend the city from Japanese invasion and by the end of 1937 the city had fallen. Chairman Mao rose to power and whispers of a newly red China rippled throughout the streets of LA's Chinatown. Hearing of the destruction and corruption of their country, May and Pearl vow to never return. They find power in their resolve. What they cannot control, though, is Joy--Pearl's college-educated, American-born daughter who feels it is her duty to witness the changes in China for herself.

It is here that See leaves the reader, but only long enough to close the book, take a deep breath, and open Dreams of Joy, the sequel.

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Sarajevo

"Irena decided that she would not shoot at someone who looked like Sting, the Princess of Wales, or Katarina Witt. She wanted to be able to enjoy looking at their pictures without seeing ghosts. She would not shoot at someone who was already wounded, though she would judge if someone limped because he had truly been wounded or because he had jammed his toe kicking a plugged-up toilet."

"Irena decided that she would not shoot at someone who looked like Sting, the Princess of Wales, or Katarina Witt. She wanted to be able to enjoy looking at their pictures without seeing ghosts. She would not shoot at someone who was already wounded, though she would judge if someone limped because he had truly been wounded or because he had jammed his toe kicking a plugged-up toilet." In April of 1992, one month after the European Union declared Bosnia's independence, Serb forces descended on Sarajevo to flush out the Muslims and create a new "ethnically pure" Serb state. This ethnic cleansing, systematic rape, and genocide would result in over 10,000 deaths and the displacement of more than 2.2 million people by December of 1995.

This fighting is the backdrop of Pretty Birds, the first novel from National Public Radio's award-winning journalist Scott Simon. The story chronicles the experiences of Irena Zaric, a Muslim star high school basketball player who loves Johnny Depp, Madonna, and her pet parrot, Pretty Bird. When asked about her tendency toward violence, Irena replies, "I'm kind of a pacifist." But when invading Serbs, led by a man called "the Knight" whose voice Irena hears at night over a loudspeaker in the nearby hills, begin to shred the pieces of Irena's life, she can no longer stand by and do nothing. To pay for food for her family she finds a job sweeping floors, but must adjust to life when her broom is replaced with a sniper rifle and she becomes a pawn of war, biding her time in abandoned buildings waiting for targets.

"Before Sarajevo," says Simon of his research, "I thought journalists were intrepid, brave, resourceful people and the universe was a decent place. It took me a long time to come to terms with what I saw there." Indeed, the same could be said for the city itself. It has now been nearly 17 years since the last sniper shot rang out in war-ravaged Sarajevo, and the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina is still realigning the pieces of itself. The city's resilience is seen in many ways, not the least of which is its push to recreate its culture through art. The National Theater has produced over 1,000 plays and more than 250 operas since its establishment in 1921. The Sarajevo Film Festival is the phoenix of the city, rising in 1995 from the smoldering wreckage of war.

Dedication to the arts is not the only reason why Sarajevo landed itself on Lonely Planet's list of top ten cities to visit in 2010. Coffee houses, artisans' shops, mosques, cathedrals, bazaars, bridges, and a long-running tram system are testaments to the ability of a people to revive the soul of a culture buried for three years in the artillery of religious hatred. Flanked by cobblestone streets on either side, the Miljacka River is the pulse of Sarajevo, a force that saw citizens through the most devastating European armed conflict since World War II and thus became a verity to which Sarajevans could set their lives.

If Simon's novel is the story of a peace-loving girl thrust into the smoke of battle, the promise of today's Sarajevo was no doubt the force that impelled her to pull the trigger.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)